BUILDING BRIDGES

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN EAST AND WEST IN SONG AND WISDOM

(This is a very slightly revised copy of a talk I gave at Hawkwood College, Stroud, on the 29th of November 2025. The subject was the astonishing links between Vedic and Celtic beliefs an d writings. These are largely illustrated in Dwina Murphy-Gibb’s Vedic Tarot, but the story reaches further than this Thanks to Caitlín and Dwina for all your wise advice.)

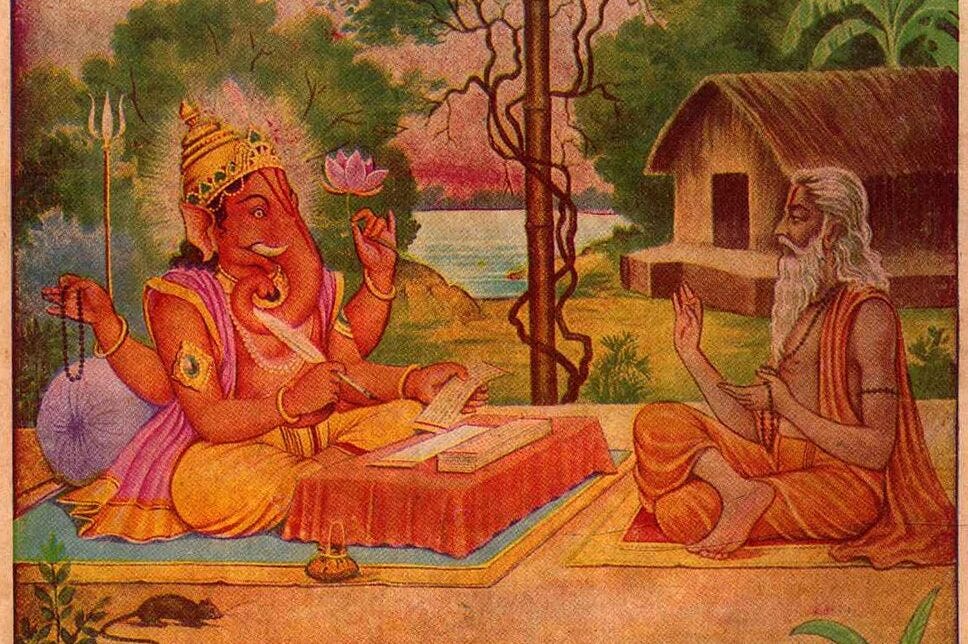

The compiler of the Vedic wisdom Veda Vyasa receiving instruction from Ganesh

I first came across the idea of a link between the Celtic and Indian people some years ago when I read the magisterial book by Alwyn and Brinley Reese called Celtic Heritage - still, in my opinion, one of the best and most important books on the subject of the Celts. There I read that...

The significance of telling the stories around the fire cannot be fully appreciated without reference to the central role of the hearth and the fire altar in Indo- European and other traditions, while the recital of tales by poets brings to mind that prose interspersed with speech poems was a narrative formed known in ancient Egypt as in mediaeval Europe, in Vedic India as in modern Ireland. (Thames & Hudson,1961).

This idea exploded like a bomb in my mind. So the Celtic traditions I loved were echoed in India.... At first I could not believe it, then I began to explore

the links between Ireland and India, between Celtic and Indian peoples, and discovered that if I crossed the divide between East and West, it all made sense. If we focus on the Indo-European world, its languages, myths and stories, we see a huge number of parallels and shared ideas. An exploration of the linguistic forms of the Irish and Indian language patterns show a number of overlaps that link the two peoples to a degree that still seems surprising.

Much has been written about the migrations of earlier peoples - with the Celts described as coming from an area somewhere between present day Russia, the Ukraine and Western Kazakhstan, or alternatively from the area of Asia minor which includes Turkey and Armenia. There are even suggestions in more recent Celtic belief, that they came from India.... an idea which may not be as unlikely as it first sounds. Most of the evidence for this comes from ancient sites scattered across Europe, and languages such as Proto-Celtic which share words with the people of India to a surprising degree. (Despite the influence of the classical world, which imposed Greek and Roman literature and myths over much of the central and western world).

To understand all of this requires a huge degree of knowledge of both traditions and especially their myths, and I continue to be greatly inspired by The Vedic Tarot, an exquisite and highly original card deck, painted and written by Dwina Murphy-Gibb ( Schiffer 2024), which is built upon both cultures and shows how many parallels we can see if we look carefully enough.

Some good examples of these links would be, first and most basic, the way both Eastern and Western societies reacted to the land on which they settled. Both regarded the earth as holy, peopling its hills and valleys, streams and shorelines with a selection of deities - gods and goddesses - who watched over the land and required rituals and sacrifices to keep it safe and empowered. No one can say how far back in time this began, but I would suggest that it originates at the time when hunter-gatherers began to farm for themselves, forming communities which depended on the earth to yield crops and sustain animals, which in turn provided both food and labour for the people.

If we take a look at the most detailed ancient texts that describe the origins of the Irish people - the Lebor Gabala Eireann or Book of the Invasions of Ireland, we learn of five waves of settlers who are variously said to originate either with Noah or his granddaughter. This clearly derives from a desire to suggest that the Celts were drawn from amongst wandering Biblical tribes, and is very doubtful, but as the Rees brothers, and other scholars since, have pointed out, the Book of Invasions itself is a late compilation, heavily influenced by the Christian monks who copied it – despite which it almost certainly contains references to much earlier times.

In the Rig Veda, the oldest known Vedic Sanskrit text, we hear of five successive waves of settlers known as the Five Kindreds. These, not unlike the tribes of incomers mentioned in Irish tradition, can be seen as spirit beings who incarnated in human form in what seems to have been an effort to raise human nature to a more spiritual level. In this they were forced to not only to give up there insubstantial bodies, but most of their spiritual selves, becoming anchored in human form.

In Ireland we hear of the coming of the Tuatha de Danaan, said to have arrived either in ships or in chariots of cloud, which are strongly reminiscent of the heavenly chariots described in the Rig Veda.

The origins of the Tuatha de Danaan go back to the God Dagda, who was descended from the goddess Anu or Danu, a goddess of rivers in Ireland, also known by this name in Hindu tradition where she is also recognised as a river goddess.

This is not the only link we find once we begin to look. In India we hear of the Dānavas, the sons of Danu, who is, like her Irish counterpart, a goddess of rivers. Could these be the same people? Both are known for their

technological powers. Māya Danava is said to have built a futuristic city in Sri Lanka and a palace in India that had within it a series of magical lakes. This may remind us of Merlin building the Round Table overnight and later erecting a magical wall of brass around Britain. Along with the sophisticated flying ships of the Tuatha this all seems very close.

We might also note the story of Tuatha de Danaan King Nuada, from Irish tradition, when he lost an arm in battle had a prosthetic silver arm made for him by his physician Dian Cécht. However, the physician’s son, who was called Miach, declared that he could do better and uttered a spell which enabled him to heal the severed limb completely.

The spell included the words

joint to joint, sinew to sinew

and within nine days and nights the arm was mended. To this day, in India, a charm used to repair fractured bones includes:

marrow shall unite the marrow

and the joints with the joints...

and the bones shall grow together again.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing is the way this idea has continued to be remembered in Ireland. As late as the 1930s a collection of Irish folklore for schools was made. It included a ‘cure’ for animals with sprained joints, still in use:

blood to blood and bone to bone

and every sinew in its own place!

Both the Tuatha and the Five Kindreds, or Dānava, are described in such a way that they possessed only partially human aspects. The story of the arrival of the magical race in Ireland is wonderfully captured in the poems of Amairgin, one of the first recorded bards, a group for which the Celts became justly famed. Amairgin invokes the power of the land itself, both claiming it for his people and calling upon the native beings who already dwelled there. He does this by showing that he is part of the land already, its seas, it’s creatures - even its herbs.

I am the wind that breathes on the sea,

I am the wave of the ocean,

I am the murmur of the billows,

I am the ox of seven struggles,

I am the vulture upon the rocks,

I am the beam of the sun,

I am the fairest of plants,

I am the wild boar of valour,

I am a salmon in the water,

I am a lake in the plain,

I am a word of science,

I am the point of the lance of battle,

I am the God who created fire in the head.

Who throws light upon the meeting on the mountain

Who announces the ages of the moon

Who teaches the place where couches the sun.....

This is astonishingly like the prayer of Lord Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita who, during a war against the Kurukshetra, declared:

I am the radiant sun among the light givers...

Among the stars of night, I am the moon...

I am Meru among mountain peaks....

I am the Ocean among waters....

I am the wind...

Of vibrations, I am the transcendental OM ...

Of immovable things

I am the Himalayas;

Of all trees, I am the holy tree.

Later Lord Krishna makes his most famous invocation

I am mighty time,

The source of destruction

That comes forth to annihilate the worlds...

I am the taste in water....

The radiance of the sun and moon.

I am the sacred syllable OM in the Vedic mantras;

I am the sound in the ether,

And the ability in all humans.

This is really laying claim to the whole of creation, it’s hills and mountains, rivers and oceans, its trees and even the stars that shine out above it. Both Amairgin and Lord Krishna are laying claim to all of creation and at the least the creative energy believed to lie at the heart of existence.

The Tuatha were remembered in all kinds of ways. Many believed that the holders of knowledge among the Celts - known as Druids - were descended from the mysterious tribe of Danu. The Irish for Druid is Draoi or Druad, both words that stem from Proto-Celtic which has similar words to Sanskrit

Dru and Vid

In the earliest forms of Irish the word dru meant ‘immersion’ or ‘total connection’, suggesting a very deep melding with the natural world or even creation itself. This is born out in shamanic traditions across the world, where the shaman partook of different aspects of the world while in a trance-journey.

Thus in the poems by the Welsh shaman-bard Taliesin we find him singing of his visionary rebirth and subsequent access to deep wisdom. He is totally connected with everything around him:

TALIESIN’S SONG OF HIS ORIGINS

Firstly I was formed in the shape of a handsome man,

in the hall of Ceridwen in order to be refined.

Although small and modest in my behaviour,

I was great in her lofty sanctuary.

While I was held prisoner, sweet inspiration educated me

and laws were imparted me in a speech which had no words;

but I had to flee from the angry, terrible hag

whose outcry was terrifying.

Since then I have fled in the shape of a crow,

since then I have fled as a speedy frog,

since then I have fled with rage in my chains,

- a roe-buck in a dense thicket.

I have fled in the shape of a raven of prophetic speech,

in the shape of satirizing fox,

in the shape of a sure swift,

in the shape of a squirrel vainly hiding.

I have fled in the shape of a red deer,

in the shape of iron in a fierce fire,

in the shape of a sword sowing death and disaster,

in the shape of a bull, relentlessly struggling.

I have fled in the shape of a bristly boar in a ravine,

in the shape of a grain of wheat.

I have been taken by the talons of a bird of prey

which increased until it took the size of a foal.

Floating like a boat in its waters,

I was thrown into a dark bag,

and on an endless sea, I was set adrift.

Just as I was suffocating, I had a happy omen,

and the Master of the Heavens brought me to liberty.

(Trans J & C Matthews)

Returning to the Irish word Dru, this also referred to a sacred oak, specifically a sacred tree of life, whose central trunk ran through the middle of the cosmos. In India this central trunk, or world access, was called Dhruva.

Vid, Weyd, or oid meant ‘knowledge’, ‘observation’ or ‘taking heed’ in Proto- Celtic. Oideas means ‘knowledge’ in modern Irish, and in Sanskrit the closely related word ‘veda’ means the same thing. So a druid was one ‘immersed in knowledge’ as were those who spoke aloud the magical and mysterious words of the Vedas.

Etymology is neither an easy nor always an advisable way of pointing out such connections, but there are so many cases here where the Irish words and its Sanskrit equivalents are so close as to make us pause. Thus for instance the Irish world word Draoi and its English derivation druid has a common root in the Hindi drishti meaning a deeply ‘focussed gaze’ or the ability to see beyond the everyday.

Both druids and Brahmins shared an important role in their respective societies: in Ireland the druids were unusually powerful - not only because they held the knowledge of the people, their history relationships and traditions ( if you wanted to marry you consulted the local druid, who could tell you at once if your relationship was too close to that of your intended) . We know that even kings were said not to be allowed to speak before a druid had spoken, and their word was quite literally law in many ways - for example if a battle was going on and a druid (or a poet ) crossed the field, not only were they sacrosanct and above harm, but often the battle would cease until they had passed. A druid could tell the leaders of warring hosts to separate the fighting warriors and cease their aggression.

The arrival of Christianity in Britain and Ireland caused the downfall of the druids, who had survived the determined destruction at the hands of the Romans (many fled to Ireland where Rome had only in minimal foothold ) Thus it was that in Ireland the role of keepers of knowledge now fell to the filí, the poets, who had always shared the position of mediators, law- keepers and knowledge- retainers, but who now moved to the forefront.

In India the same structure held true. A distinct division existed between the brahmarsi or ‘poet-priests’ who composed religious verse, and the rajarsi or ‘warrior poets’, who composed great verse epic such as the Mahabarata. Interestingly, the word to the rajarsi are the Irish rigfilis or ‘kingly poets’ while the word rí means ‘king’ in Irish.

Thus the ‘kings’ or rajas of India ruled with the help of local Brahmin judges, drawing on the Book of Manu; while in Ireland the king or rí was supported by Brehon judges, drawing upon the Brehon Laws. The Indo-European root word berrih, meaning ‘to carry’ or to ‘bring forth’, gives us breth in Irish, meaning ‘carrier of judgments’ , while Brahmin can be understood to mean ‘keeper of mantras’ in India.

In the realm of poetry itself we find parallels everywhere, reflected in the rich collections of what we may think of as the knowledge texts. The most obvious of these is once again the Welsh poet Taliesin, whose poems, much fought over for meaning, date and actual authorship, gathered a huge set of references to Celtic law and tradition. One of these, on the subject of knowledge and inspiration, has recently been translated by Caitlín Matthews

TALIESIN CONSIDERS INSPIRATION

1. I entreat my Lord

That I may consider inspiration:

What brought awen forth

Before the time of Ceridwen?

At the beginning of the world

What necessity brought it forth?

You monks who read,

Why don’t you tell me,

Why don’t you confront me,

Now that you don’t pursue me?

2. What made smoke to rise?

What engendered evil?

What fountain radiates beauty

Above the cover of darkness?

Whence comes autumn?

Whence comes a moonlight night,

But then another so dark you can

Scarce perceive a shield outside?

Why is it so noisy,

The waves’ tumult striking the shore?

It is the vengeance of Dylan

Reaching towards us.

3.Why is a stone so heavy?

Why is a thorn-bush so sharp?

Do you know what is better –

Thorn’s base or thorn’s tip?

What made a covering

Between man and the cold?

Whose death is better –

That of a youth or an aged one?

4. Do you know what you are

When you are asleep

A body or a soul,

Or a white shimmering thing?

O skilful singer,

Won’t you tell me?

Do you know where

Night waits for the day?

How many leaves are there on the trees?

What raised up the mountain

Before the world’s undoing?

What supports the abode

Of the earth unceasingly?

5. The lamented soul,

Who saw it, who recognised it?

I am amazed that books

Don’t know for certain

Where the soul has its dwelling,

After the body’s burial.

From which region pours out

The great wind and the strong stream

In deadly combat,

Endangering the poor soul?

I wonder in song,

Whence came the lees

And whence the intoxication

From mead and braggart

What caused their destiny

Save God the Trinity?

6. Of whom should I declaim

Except of the Three?

What created a coin

From rounded silver?

Why is a cart’s career

So very crooked?

Death lies under all,

And is dispensed in every land;

Death is above us –

Wide its winding sheet,

Higher than heaven’s roof-tree;

Man is older when born

Growing younger all the time.

7. Anxiety stalks us still

Over the world’s declining.

After such great gifting

Why were we made so short-lived?

It is sadness enough,

To be lodged in a grave.

May he who made us,

He of the highest realm,

May he bring us peace

And gather us in at the end.

Much of the poetry of both cultures was designed to be spoken, or indeed sung or chanted at important gatherings, and it is notable that in both instances, where the stories, such as those told in the Rig Vedaand the Irish texts, there is often a mix of prose and verse. While the Irish seanachies or storytellers were allowed to vary the words in which the tales were written, the verse segments had to be learned by heart and repeated exactly. In the manuscripts that have survived the verse sections are often written in a much more ancient version of the language. The same is true of the Brahmans who sang or chanted long experts from the Mahabarata (much as the Greeks did with the Homeric epics) and have continued to do so right up to the present. Thus the Voyage of Bran, in which the titular hero is invited by a woman of Faery to voyage in search of wisdom, is almost entirely in verse

“One day, in the neighbourhood of his stronghold, Bran went about alone, when he heard music behind him. As often as he looked back, still behind him the music was. At last he fell asleep at the music, such was its sweetness. When he awoke from his sleep, he saw close by him a branch of silver with white blossoms, nor was it easy to distinguish its bloom from that branch. Then Bran took the branch in his hand to his royal house. When the hosts were in the royal house, they saw a woman in strange raiment on the floor of the house. Then it was that she sang the fifty quatrains to Bran, while the host heard her, and all beheld the woman.

And she said:

‘A branch of the apple-tree from Emain

I bring, like those one knows;

Twigs of white silver are on it,

Crystal brows with blossoms.

‘There is a distant isle,

Around which sea-horses glisten:

A fair course against the white-swelling surge,

Four feet uphold it.

‘A delight of the eyes, a glorious range,

Is the plain on which the hosts hold games:

Coracle contends against chariot

In southern Mag Findargat.

‘Feet of white bronze under it

Glittering through beautiful ages.

Lovely land throughout the world’s age,

On which the many blossoms drop.

‘An ancient tree there is with blossoms,

On which birds call to the Hours.

’Tis in harmony it is their wont

To call together every Hour.

‘Splendours of every colour glisten

Throughout the gentle-voiced plains.

Joy is known, ranked around music,

In southern Mag Argatnél.

‘Unknown is wailing or treachery

In the familiar cultivated land,

There is nothing rough or harsh,

But sweet music striking on the ear.

‘Without grief, without sorrow, without death,

Without any sickness, without debility,

That is the sign of Emain

Uncommon is an equal marvel.”

(Trans by Kuno Meyer)

This is full of Celtic magic of course; but so are the poems which make up more than half of the Mahabarata, which are still sung. Here is a short extract in a delightful 18th century translation by Veda Vyasa. It concerns the hero and sage Drona. A master of advanced military arts and the divine weapons known as astras, Drona initially chooses a life of poverty but later serves as the second commander-in-chief of the Kaurava army, from the 11th to the 15th day of a huge battle. He is eventually slain and when he feel his death coming upon him he begins to meditate and release his soul on the battlefield in a manner that curiously reflects the death of the Irish hero Cuchulain.

Here he rouses the warriors to prepare for the oncoming war:

Out spake Drona priest and warrior, and his words were few and high...

‘Thou hast heard the holy counsel which the righteous Krishna said,

Ancient Bhishma’s voice of warning thou hast in thy bosom weighed,

Peerless in their godlike wisdom are these chiefs in peace or strife,

Truest friends to thee, Duryodhan, pure and sinless in their life!

Take their counsel, and thy kinsmen fasten in the bonds of peace,

May the empire of the Kurus and their warlike fame increase,

List unto thy old preceptor! Faithless is thy fitful star,

And they feed thy passions falsely, those who urge and counsel war!

Crownéd kings and arméd nations will contest for thee in vain,

Vainly brothers, sons, and kinsmen will for thee their lifeblood drain,

(Mahabharata, Book VI - Drona’s Speech)

To hear this is just like hearing a Celtic bard or Filí reciting one of the epics of his tribe. Full of the same dash and vigour.

We don’t need to look very far to see the many bridges between these distant-seeming cultures. Just a single further example should demonstrate this. I think most of you will be familiar with the stories of supernatural suitors, where either a male or female faery comes from the otherworld in search of a human husband or bride. You can find these in many examples across Ireland and Wales, but if you look at the Rig Veda you find references to the Gandharvas who act as rivals who dispute the bridegroom’s possession of the bride. It’s also mentioned that the presence of the Gandharva is considered necessary to enable conception. The references to these in the Rig Veda show them to be spirits of the air or of the waters, while other texts associate them with mountains, caves, and forests, with the world of the dead, and with animals. They are usually seen half man and half bird. Their wives or mistresses appears as water nymphs. The Gandharvas also have charge of Soma, or they steal it – Soma being the magical brew that fuels human and Gods alike and which is sought in many versions in the same way as the Grail is in western tradition.

From all of this we can see how close the two cultures were - and indeed still are - and how perfectly The Vedic Tarot demonstrates this

§§§§

Here is the meditation which followed the talk. Sadly you cant hear Catlín’s voice supplying some of the music, but let your inner self hear the song of the stars.

BRIDGES BETWEEN WORLDS

A MEDITATION

Close your eyes and take some deep breaths. Let your sense of this room fade. Find yourself standing on the bank of a wide and free-flowing river. As you look into it you see the reflection of yourself as you truly are, and behind your head a range of stars scattered across the heavens.

After a moment you are urged to step into the water - not to be carried off by the racing water, but to be carried up, up into the starry sky...

Now you are walking in a second river, one that leads across the cosmos into the furthest distance. Take a moment to adjust to the change, then look around you.....

You see, on either side, two rivers, one shot through with gold, the other with silver, in which fish swim alongside floating stars. Linking the two rivers is a bridge, built of ancient stones. You step onto this and at once your vision changes.

Now you see how the two rivers contain beings of both Celtic and Vedic origin -some of whom seem to coalesce into a single figure. Some are so huge that they stretch up into the starry night; others are smaller than us.....

They see you, see us all, and from amongst this throng come two figures- one clad in the robes of a Celtic Bard, the other in those of a Vedic Seer. Both will come to you and speak with you. You may ask your question and receive an answer from either, or both. They may offer to teach you more. The choice is yours...

Now third figure emerges, a curious being, part human part creature, such as you may never have seen before..... It holds a mirror between its hands and as it draws near it holds this it up so that you can see yourself. As in the reflection you saw in the river, this shows you as you truly are. You may see changes that have already begun from deep within...

Now, as you stand in the presence Of these mighty teachers, you hear sounds that you recognise as music, though such as you may never have heard before.

The sound rises to a great chorus as though voices were coming from all parts of the cosmos. You feel that your innermost self joins in this great song....

When you are ready, take your leave of the teachers and find yourself again floating in the river you first saw ... Step ashore when you are ready and, in your own time, awaken again to the room where you began.

John Matthews, 2025

Beautiful. I work with a number of Hindu students and their spirit is fascinating. I like the comparisons of Sanskrit to Irish Gaelic.

Thank you Jonathon. You need to read the book called Taliesen’s Map by J Dolen. It’s stunning and very much the kind of thing we were trying to convey over the weekend! Many blessings. J