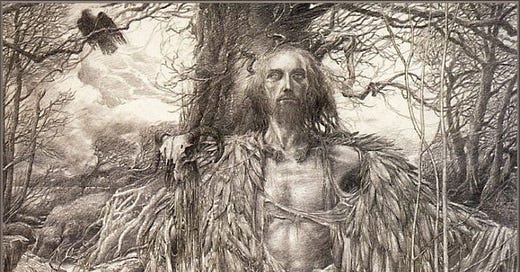

Merlin the Wild by Alan Lee

MERLIN THE SHAMAN

We are used to thinking of Merlin as a medieval magician, the man who arranged the birth of Arthur,who created a round table, who set the sword in a stone, who performed feats of magic before being shutunder a stone or in a cave by the vengeful fairy Nimue. But there is another Merlin, who was therebefore that - an older Merlin whose life and deeds are very different from those of his medievalsuccessor. It is at this figure of Merlin and that I want to look today. Not Merlin the magician - butMerlin the shaman.

Merlin has in fact been perceived in many different ways by the writers, artists and storytellers who have portrayed him over the centuries. But in our own time, researchers and historians seeking his roots have turned to the figure of the shaman for the oldest aspect of his character.

The first shamans fulfilled many of the roles later attributed to Merlin: they were lore keepers, healers, prophets, diviners and ceremonialists, as well as ambassadors to and interpreters of the gods. A shaman was born, not made; he was literally a walker between the worlds, one whose attunement to both tribal consciousness and the spirits was so fine that he or she could slip between the hidden parallels of life and death, between the worlds and report on what they saw there. It is upon the shaman's revelations and visions that much of our oldest known religious practices and beliefs are founded. While tribal members had only a vague notion of the threshold dividing the worlds, the shamans could not only divine future events through interaction with the spirits of nature and of elemental forces, but were also supremely sensitive to the will of the ancestors, the first gods. The oldest stories of deity arose from a weaving of relationships between such animistic powers and the people who understood and interpreted them.

In each of these aspects of the Shaman we can find something of the character and actions of Merlin. He too is a mover and shaper, a seer who offers profound insights into the inner worlds of the spirit. Even in the later, medieval figure of the magician, weaving his spells and shaping the destiny of Arthur and his people, we can catch a glimpse of the shaman, while in the earliest records in which the name Merlin appears it is central to his character.

Merlin the Magus by Andrey Shishkin

These early records can be enigmatic and offer a number of problems for anyone seeking the origins of Merlin. Many were not written down for several hundred years after they were first composed, in the form of poems meant to be spoken or sung by court bards in the halls of early Welsh chieftains. Since oral tradition is notoriously difficult to establish, this makes the evidence for the actual existence of Merlin equally hard to prove. Favorable to this is the rigorous discipline of memorizing vast amounts of poetry practiced by the early bards. Distrusting writing, they committed everything they composed to memory, ensuring that the versions that were written down by later transcribers are more likely to be accurate, at least to a reasonable degree.

With these provisos in mind we may look at the earliest records in which the name or character of Merlin makes an appearance in shamanic guise, always keeping in mind that within this shifting tapestry of words and images, we can do no more than catch a glimpse of our pray.

The first recorded mention of the name Merlin (in its Old Welsh form Myrddin or Mirdyn ) appears in one of the oldest surviving pieces of epic Celtic literature - a 9th century poem called Y Gododdin (The Gododdin), which describes a fateful expedition of a band of warriors from an area close to modern day Edinburgh, to a place known as Catraeth (identified as lying close to the North Yorkshire town of Catterick), where they fight a battle against the Saxons in which almost all are slain. Among those mentioned by name is a warrior called 'Mirdyn', though nothing more is said of his character or role, and we have no means of knowing whether this character is in any way related to the more famous Merlin.

Another Welsh poem, the Armes Prydein (Prophecy of Britain) which dates from roughly the same period as The Gododdin, uses the phrase 'Dysgogan Myrdin', 'Merlin foretells' as the opening words to several of its stanzas. The poem foretells various events that are to come and establishes Merlin as a prophet right from the start.

These brief references suggest that the name Merlin was known as long ago as the 8th or 9th centuries - possibly earlier since these references had almost certainly been preserved in oral tradition for several hundred years before this. Again, whether this Merlin has or had anything to do with the later character, the references are intriguing enough to give us pause for thought.

Elsewhere, in a collection of poetic triplets used by the native British bards as a kind of aide memoir for storytellers and poets, we also find mention of Merlin, who is even given a pedigree of sorts. These enigmatic writings, known as Trioedd Ynys Prydein ( The Triads of Britain), date in manuscript from the 13th century, but their origins are once again much earlier - being traceable to 6th century sources at least, or even earlier if we refer them to oral tradition. Triad 87 lists

Three Skillful Bards of Arthur's Court:

Myrddin son of Morfren.

Myrddin Emrys,

and Taliesin.

This reference is particularly important as it is the first time that Merlin is associated with Arthur, as well as suggesting that there may have been more than one Merlin. We should also note that here Merlin is presented as a bard, a role which at this point in time was assumed to include not only the ability to write poetry and to sing, but also to posses prophetic insight.

In his next appearance in the early literature of Wales, Merlin is not only a poet but also a warrior. A few enigmatic references, scatted through a collection of medieval poems, some of which are actually attributed to Merlin himself, tell us a little more, and hint at a story which was only to be fully told in the 11th century.

The Black Book of Carmarthen is one of four collections of early Welsh poetry now held in the National Library of Wales and known collectively as The Four Ancient Books of Wales. The manuscript dates from the 13th century, but like many of these texts, contains material which originated much earlier. Within the collection are several poems said to have been written by someone named Myrddin They may well date from well after the time of any real historical character who bore this name, and there is no direct evidence to suggest that this Myrddin is the same as the more familiar character - however, there are aspects of the story glimpsed between the lines of the poems which were destined to become a central part in the developing story of Merlin.

Essentially there are three poems which we need to look at here - they are more personal than the rest, which are either prophetic or political. The first of the three is called Oianau (Greetings). It describes a man living alone in a wild forest, apparently the Wood of Celyddon - the great Caledonian forest which once stretched over more than half the land between the Grampian mountains and the old Roman wall built at the command of the Emperor Hadrian. The poem is addressed to his only companion, a pig.

Listen, little pig,

O happy little pig!

Do not go rooting

On top of the mountain,

But stay here,

Secluded in the wood,

Hidden from the dogs

Of Rhydderch the Faithful.

I will prophecy -

It will be truth! -

From Aber Taradyr

The Cyrmy will be bound

Under one warlike leader

Of the line of Gwynedd.

Usurpers of the Prydein

He will overcome…..

Listen, little pig,

We should hide

From the huntsmen of Mordei

Lest we be discovered.

If we escape -

I'll not complain of fatigue! -

I shall predict,

From the back of the ninth wave,

The truth about the White One

Who rode Dyfed to exhaustion,

Who built a church

For those who only half believed.

From these enigmatic verses we learn a number of things. Firstly, the poet is living alone in the forest, an outcast in fear of his life, hiding from 'the dogs of Rhydderch' and the 'huntsmen of Mordei'. He is cold, hungry and has endured 'fifty years of pain' because of the death of a man named Gwenddolau, in battle at a place named Arderydd, and above all because of the absence of someone named Gwenddydd.

The information contained in this poem may not seem much. But if we look more closely at some of the details and put them together with those in the other poems attributed to Myrddin, a picture begins to emerge.

First of all, there are the names: Rhydderch is almost certainly to be identified with Rydderch Hael (the Generous) an historical figure who lived towards the end of the 6th century AD. A prominent chieftain, he is mentioned in a number of early documents, in particular the Life of St Columba, written by Adamnan, which refers to him ruling over Strathclyde during the life-time of the saint. Since Columba died in 597 this places Rhydderch clearly in the 6th century, when Merlin is believed to have lived, in an area not far from the apparent setting of the poems.